Max Weber: "La ética protestante y el Espíritu del Capitalismo"

Max Weber: "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism"

ENGLISH VERSION BELOW

Analizamos el clásico libro de Guiddens, y las consecuencias indeseadas de la teoría de la predestinación Calvinista y la ascesis de lo mundano, que tuvo como consecuencia indeseada el surgimiento del espíritu del capitalismo moderno.

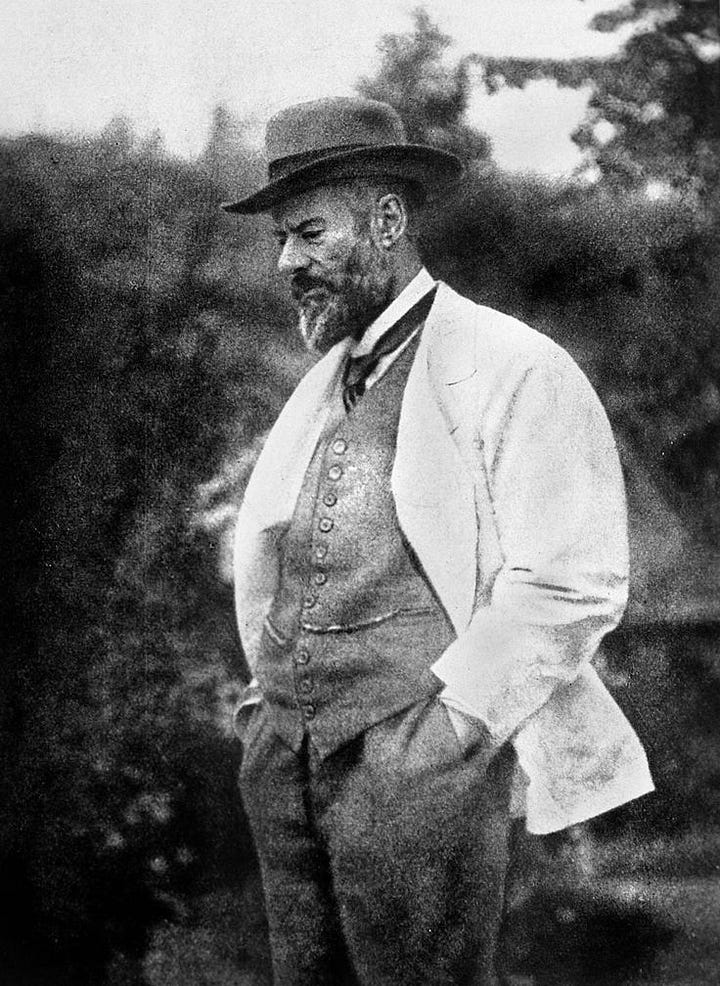

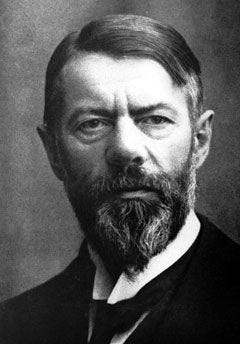

Max Weber, era hijo de un jurista del partido nacional y de una calvinista devota. Entre sus padres había dos estilos de vida bien diferenciados. El padre jurista llevaba una vida mundana que evitaba todo compromiso y su madre por su parte era devota de llevar una vida ascética, que evitaba los placeres terrenales.

Esto caló profundamente en el pensamiento de Weber que se interesó por indagar en los orígenes de la filosofía protestante, que lo llevaría a escribir su libro más importante: "La ética protestante y el Espíritu del Capitalismo".

Para escribirlo, comenzó analizando los sistemas religiosos de varios países, entre ellos Alemania. En ellos vió que los líderes del sistema económico que la burguesía, los trabajadores asalariados eran en su mayoría protestantes. Estas elecciones de vida y profesiones capitales están basadas en la Fe protestante. Por su parte, la religión católica no promovía ideas burguesas, como el deseo de ser los dueños del capital.

Cómo estadística, usó la estadística confesional de Badén, que fue realizada por su discípulo Martín Offenbacher. El mismo consistía en analizar la situación económica de los protestantes y de los católicos de dicha región, y encontró que en 1895 los protestantes tributaban mucho más que los católicos. Había también mas estudiantes protestantes en Colegios técnicos avanzados, que católicos o judíos, de ahi que Weber afirmó: "Los Católicos demuestran una inclinación mucho más fuerte a seguir en el oficio, en el que suelen alcanzar el grado de maestros, mientras que los protestantes se lanzan en número mucho mayor a la fábrica, en la que escalan los puestos superiores del proletariado ilustrado y del burocracia industrial.” Tomando el refrán, "Comer bien o dormir tranquilo" deduce que el protestante opta por comer bien y el católico por dormir tranquilo, afirmando que los católicos querían una vida más tranquila con menores salarios, y los protestantes preferían trabajar más a cambio de mayor poder adquisitivo.

Así Weber realiza la afirmación de que a partir de la ética protestante, nació el espíritu del capitalismo, pero no su sistema, (el cual quizá pueda considerarse como un efecto indeseado de la ética protestante). Él habla en su libro de una forma de pensar, que ayudó al avance del capitalismo, no de sus consecuencias.

Se pregunta en su libro, ¿Qué es la ética protestante?. Para responder a esta pregunta, Weber descubre que la palabra alemana Beruf (profesión) y que la palabra inglesa "Calling" (vocación/llamado), surgieron durante la reforma protestante, sin existir palabra similares o sinónimos en la Edad Media o la Antigüedad. Estas palabras, tuvieron una fuerte reminiscencia religiosa, ya que ambas palabras implican que hay un deber de mandato de un cumplir un deber impuesto por Dios. Lutero introduce esta idea de "Beruf" para que interioricen las personas estas palabras, como mandatos de Dios. Si bien Lutero fue importante, no fue decisivo a la hora de introducir el espíritu del capitalismo, ya que su concepción de vocación fue sumamente estática, ya que para el luteranismo ya que el ejercicio de una profesión concreta, constituye un mandato dirigido por Dios, por la cuál obligaba a todo creyente a permanecer en la situación en que se encontraba. Por ejemplo para Lutero, el que nació campesino, debía morir como campesino.

Weber entonces aclara que no fueron todas las éticas protestantes, sino algunas de ellas, entre las cuáles se encuentran el Calvinismo, el Pietismo, el metodismo y algunas sectas del Baptismo. A partir de esto, sentenció que la más influyente fue el Calvinismo, y más que nada el puritanismo inglés del teólogo Richar Baxter (1615-1691). Luego de esta mención, para comprender mejor la ética protestante, Weber toma analiza dos conceptos

Predestinación

Ascetismo

La doctrina de la predestinación de Juan Calvino, consiste en que todos estamos predestinados a ir al cielo o al infierno, y no hay nada ni nadie que pueda alterar la decisión soberana de Dios acerca de quiénes se salvan y quienes no. Por lo tanto, no importa lo que hagamos, no importa cómo nos comportemos o qué actos realicemos, ya que Dios decidió desde el origen del universo quienes son los elegidos. Weber sostuvo que por esta doctrina, los calvinista sufrieron una gran ansiedad psicológica, porque provocó en ellos la constante duda de si estaban o no salvos. Para enfrentar esto, los calvinistas del siglo XVII, desarrollaron una teoría que consistía en una serie de signos para saber si uno podía ser salvo o no. Esos signos tenían que ver con el éxito económico y profesional. Por esto, para los calvinistas era fundamental que las personas trabajen con esfuerzo y ahínco, porque si eran constantes iban a descubrir las señales de salvación. Entonces, Weber define una serie de efectos que genera la teoría calvinista:

A. Los Calvinistas se emplean en una actividad profesional intensa

B. Utilizan la razón para ser más eficientes en el plano económico.

C. Al combinar ambos, lograrían el éxito económico y la seguridad de salvación.

Para terminar de comprender al Calvinismo, hay que comprender la ética ascética de los calvinistas mencionada anteriormente. La ética ascética, consiste en un estilo de vida disciplinado, austero y de renuncia a los placeres mundanos. Llevar una vida estricta, sencilla y sin lujos, porque la vagancia y los placeres terrenales son tentaciones pecaminosas que alejan a las personas de la gracia de Dios y de la vida espiritual. Por lo tanto, la acumulación de capital, no era para tener una mejor calidad de vida llena de lujos, sino para glorificar a Dios y de estar seguro de estar entre los elegidos por este. El éxito económico y la vida ascética promovieron actividades como el ahorro, la acumulación de capital y la inversión.

Luego de dejar bien en claro la relación de la ética del Calvinismo con el espíritu del capitalismo, Weber pasa a explicar esto último.

Para Weber, el espíritu del capitalismo, no consiste solo en acumular riquezas, ya que este deseo existió siempre en todas las civilizaciones. En segundo lugar, dice que el espíritu del capitalismo, llegó a ser un sistema ético y moral, un "ethos" que ensalzó el éxito económico de aquí que el mundo occidental, se haya diferenciado del resto del mundo, ya que el calvinismo consiguió que el beneficio se transforme en un acto moralmente aceptable. En otras sociedades, según Weber, el deseo de obtener más riquezas era visto como algo avaro, individualista y moralmente sospechoso. Define al espíritu del capitalismo, como un sistema normativo que implica un conjunto de ideas sistematizadas. Ejemplo: Su objetivo consiste en infundir una actitud que persiga el beneficio racional y sistemáticamente también predica la renuncia de los placeres terrenales y lleva ideas implícitas como "El tiempo es dinero", "Tienes que ser laborioso", "tienes que ser puntual"; "tienes que ser sobrio", "tienes que prosperar", en síntesis, que ganar dinero es un fin en sí mismo.

Además de los resultados de la estadística de Baden, Weber recurrió a Bejamin Franklin. Benjamin Franklin, profesaba un deísmo desteñido, nos contestaría con una expresión bíblica, inculcada desde la infancia por su padre, del cual aseguraba que era un recalcitrante calvinista. "¿Has visto hombre solícito en su trabajo?. Delante de los reyes estará." El ganar dinero, en la medida que se lo haga legalmente, es dentro del moderno orden económico, el resultado y la expresión de la idoneidad en la profesión, y esta idoneidad, como es fácil advertir, constituye alfa y omega de la moral de Franklin, tal como surge de los fragmentos citados y de todos sus escritos sin excepción.

A partir de esta cita, el trabajo para Franklin como actividad adquisitiva y la ganancia como ahorro aparecen no como medios, sino como fines en sí éticamente sancionados, en síntesis la ganancia legal para Franklin, fue el resultado y la expresión de la virtud humana.

Hay que aclarar, que Weber nunca dijo que gracias a la ética protestante surgió el sistema capitalista. De hecho Weber, ubicó el surgimiento del capitalismo en la Baja Edad Media. Lo que sí señaló Weber, es que la ética calvinista tuvo una importante influencia y afinidad electiva con el espíritu del capitalismo. Si sentencia, que el origen del espíritu del capitalismo, se encuentra en la ética protestante, más precisamente en los puritanos ingleses del siglo XVII.

Siguiendo dijo que el espíritu del capitalismo no debe ser entendido como una causa directa del Calvinismo, ya que Calvino y los calvinistas jamás tuvieron el deseo de crear un espíritu funcional al capitalismo. El espíritu del capitalismo, más bien fue una consecuencia imprevista por los calvinistas. Esto es importante para Weber, porque demuestra que las acciones suelen tener consecuencias distintas de sus intenciones.

Hay que recordar que además del calvinismo, en la formación del espíritu calvinistas, otras ramas protestantes fueron importantes como el Pietismo, el Baptismo.

La razón clave del calvinismo fueron su ética de la predestinación y su ética ascética intramundana.

La interpretación de Guiddens.

El sociólogo británico Anthony Guiddens, publicó "El capitalismo y la moderna Teoría Social". En el mismo Giddens, da una visión distinta de la de Max Weber sobre la doctrina de la predestinación y sus consecuencias. Ante la ansiedad psicológica de la predestinación, los calvinistas ofrecieron dos respuestas relacionadas entre sí.

Primero tenían que tener una fe inquebrantable, ya que dudar sobre su salvación era una muestra de fe imperfecta, y por ende de carencia de gracia.

La intensa actividad en el mundo, era la mejor manera para desarrollar y mantener la necesaria seguridad de salvación.

Así Giddens, explica que Weber señaló que la realización de buenas obras era para los calvinistas un signo de salvación, no un método para ganarse la salvación, sino una forma de eliminar las dudas acerca de si eran salvos ya que el buen comportamiento y la laboriosidad profesional eran síntomas de estar glorificando mejor a Dios, y por ende de ser salvo. Por eso la señal de salvación, no se encuentra en el éxito económico sino en la realización de buenas obras y en el cumplimiento ascético del deber profesional. La acumulación de riquezas y el éxito profesional, fue el éxito de la ética de los calvinistas.

We analyze Guiddens' classic book and the unintended consequences of Calvinist predestination and the asceticism of the worldly, which led to the rise of the spirit of modern capitalism.

Max Weber was the son of a National Party jurist and a devout Calvinist mother. His parents shared two distinct lifestyles. His jurist father led a worldly life that avoided all commitment, and his mother, on the other hand, was devoted to leading an ascetic life that avoided earthly pleasures.

This deeply influenced Weber's thinking, and he became interested in exploring the origins of Protestant philosophy, which would lead him to write his most important book: "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism."

To write it, he began by analyzing the religious systems of several countries, including Germany. In them, he saw that the leaders of the economic system—the bourgeoisie, the wage workers—were mostly Protestants. These life choices and capital professions were based on the Protestant faith. Catholicism, on the other hand, did not promote bourgeois ideas, such as the desire to own capital.

As a statistic, he used the confessional statistics of Baden, developed by his disciple Martin Offenbacher. This consisted of analyzing the economic situation of Protestants and Catholics in that region, and found that in 1895, Protestants paid much more taxes than Catholics. There were also more Protestant students in advanced technical colleges than Catholics or Jews, hence Weber stated: "Catholics show a much stronger inclination to remain in the trade, where they usually reach the rank of teacher, while Protestants in much greater numbers head to the factory, where they rise to the upper ranks of the educated proletariat and the industrial bureaucracy." Taking the proverb, "Eat well or sleep well," he deduces that Protestants choose to eat well and Catholics choose to sleep well, stating that Catholics desired a quieter life with lower wages, and Protestants preferred to work more in exchange for greater purchasing power. Thus, Weber asserts that the spirit of capitalism was born from the Protestant ethic, but not its system (which could perhaps be considered an unintended effect of the Protestant ethic). In his book, he speaks of a way of thinking that contributed to the advancement of capitalism, not of its consequences.

In his book, he asks, "What is the Protestant ethic?" To answer this question, Weber discovers that the German word "Beruf" (profession) and the English word "Calling" (vocation/calling) emerged during the Protestant Reformation, with no similar words or synonyms existing in the Middle Ages or Antiquity. These words had a strong religious connotation, as both words imply that there is a duty mandated by God to fulfill a duty imposed by God. Luther introduced this idea of "Beruf" so that people would internalize these words as commands from God. While Luther was important, he was not decisive in introducing the spirit of capitalism, as his conception of vocation was extremely static. For Lutheranism, the exercise of a specific profession constitutes a mandate directed by God, which obliged every believer to remain in the situation in which they found themselves. For example, for Luther, anyone born a peasant should die a peasant.

Weber then clarifies that not all Protestant ethics were included, but rather some of them, including Calvinism, Pietism, Methodism, and some Baptist sects. From this, he concluded that the most influential was Calvinism, and especially the English Puritanism of the theologian Richard Baxter (1615-1691). After this mention, to better understand the Protestant ethic, Weber analyzes two concepts:

Predestination

Asceticism

John Calvin's doctrine of predestination states that we are all predestined to go to heaven or hell, and nothing and no one can alter God's sovereign decision about who is saved and who is not. Therefore, no matter what we do, how we behave, or what actions we perform, God decided from the beginning of the universe who the elect are. Weber argued that this doctrine caused Calvinists to suffer great psychological anxiety because it caused them to constantly doubt whether or not they were saved. To address this, 17th-century Calvinists developed a theory consisting of a series of signs that determined whether one could be saved. These signs had to do with economic and professional success. Therefore, for Calvinists, it was essential that people work hard and diligently, because if they were persistent, they would discover the signs of salvation. Weber then defines a series of effects generated by Calvinist theory:

A. Calvinists engage in intense professional activity.

B. They use reason to be more efficient economically.

C. By combining both, they would achieve economic success and assurance of salvation.

To fully understand Calvinism, one must understand the ascetic ethic of Calvinists mentioned above. The ascetic ethic consists of a disciplined, austere lifestyle that renounces worldly pleasures. Lead a strict, simple, and luxurious life, because laziness and earthly pleasures are sinful temptations that distance people from God's grace and the spiritual life. Therefore, the accumulation of capital was not intended to achieve a better quality of life filled with luxuries, but to glorify God and be assured of being among His chosen ones. Economic success and an ascetic life promoted activities such as saving, capital accumulation, and investment.

After clearly explaining the relationship between Calvinist ethics and the spirit of capitalism, Weber goes on to explain the latter.

For Weber, the spirit of capitalism does not consist solely of accumulating wealth, as this desire has always existed in all civilizations. Secondly, he argues that the spirit of capitalism became an ethical and moral system, an "ethos" that extolled economic success, which is why the Western world differentiated itself from the rest of the world, as Calvinism managed to transform profit into a morally acceptable act. In other societies, according to Weber, the desire for greater wealth was viewed as greedy, individualistic, and morally suspect. He defines the spirit of capitalism as a normative system that involves a set of systematized ideas. Example: Its objective is to instill an attitude that pursues rational profit, and it also systematically preaches the renunciation of earthly pleasures and carries implicit ideas such as "Time is money," "You must be industrious," "You must be punctual," "You must be sober," "You must prosper"—in short, that making money is an end in itself.

In addition to the results of Baden's statistics, Weber turned to Benjamin Franklin. Benjamin Franklin, professing a faded deism, would answer us with a biblical expression, instilled in him from childhood by his father, whom he claimed was a recalcitrant Calvinist. "Have you seen a man diligent in his work? He will stand before kings." Earning money, to the extent that it is done legally, is, within the modern economic order, the result and expression of professional fitness. This fitness, as is easy to see, constitutes the alpha and omega of Franklin's morality, as it emerges from the cited fragments and from all his writings without exception.

From this quote, for Franklin, work as an acquisitive activity and profit as savings appear not as means, but as ethically sanctioned ends in themselves. In short, for Franklin, legal profit was the result and expression of human virtue.

It should be clarified that Weber never said that the capitalist system emerged thanks to the Protestant ethic. In fact, Weber located the emergence of capitalism in the Late Middle Ages. What Weber did point out is that the Calvinist ethic had an important influence and elective affinity with the spirit of capitalism. He did, however, conclude that the origin of the spirit of capitalism is found in the Protestant ethic, more specifically in the English Puritans of the 17th century.

He went on to say that the spirit of capitalism should not be understood as a direct cause of Calvinism, since Calvin and the Calvinists never had the desire to create a spirit functional to capitalism. Rather, the spirit of capitalism was an unforeseen consequence for the Calvinists. This is important for Weber because it shows that actions often have consequences distinct from their intentions.

It should be remembered that, in addition to Calvinism, other Protestant branches, such as Pietism and Baptistism, were important in the formation of the Calvinist spirit.

The key reasons for Calvinism were its ethic of predestination and its ascetic inner-worldly ethic.

Guiddens' interpretation.

British sociologist Anthony Guiddens published "Capitalism and Modern Social Theory." In it, Giddens offers a different view from Max Weber on the doctrine of predestination and its consequences. Faced with the psychological anxiety surrounding predestination, Calvinists offered two interrelated responses.

First, they had to have unshakeable faith, since doubting their salvation was a sign of imperfect faith, and therefore a lack of grace.

Intense activity in the world was the best way to develop and maintain the necessary assurance of salvation.

Thus, Giddens explains that Weber pointed out that for Calvinists, performing good works was a sign of salvation, not a method to earn salvation, but a way to eliminate doubts about whether they were saved, since good behavior and professional industriousness were symptoms of better glorifying God and therefore of being saved. Therefore, the sign of salvation is not found in economic success but in the performance of good works and the ascetic fulfillment of professional duty. The accumulation of wealth and professional success were the hallmarks of Calvinist ethics.